By Rosamund Looney

My first grade classroom—normally sleepy—is already buzzing when I walk in during breakfast time.

“Ms. Looney, I brought something very exciting to share with the class!”

“OK,” I say cautiously. “What is it?”

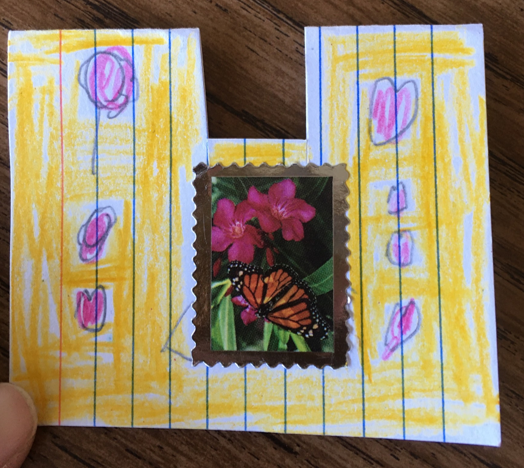

A pencil box opens and countless folded index cards fly out of it, each with a square carefully cut out of the middle. “Oh,” I say, surprised. “What are those?”

“Wallets! For everyone!” The child grins, holding one out to me: an index card, folded in half, with a square cut from the fold. I squint at it. As an adult, it’s difficult to get inside the wild mind of a 6-year- old. I imagine the hole must signify a money clip on the outside of a leather wallet. “My dad has a wallet with lots of money in it. Can I pass out my wallets now or later?” the student asks anxiously.

I tell the child I need to think for a bit. I set my things down, pondering safety protocols and how they apply to imagined paper wallets. The district has recently cleared school librarians to begin checking out books to students again. But sharing anything is banned this year. And yet, how much harm could an index card cause? I relent, and the child passes them out. When one student arrives to class late, he finds a paper wallet resting on his pencil box. “What’s this?” he asks, entranced by an item he immediately knows to be of great value.

During each of our breaks, most of the students choose to decorate their wallets. The colored pencils and crayons come out; secret stashes of stickers emerge. The class feels excited and happy.

The next day brings a new adventure.

“I have those things!” shouts a student as soon as I enter the room. I’m flummoxed. It’s 7:15 a.m. “What things?” The student excitedly opens his pencil box to reveal a pile of small, roughly cut bits of white paper.

“You know, those things!” he says, beginning to lose a little of his light, with frustration searching for the right word, any word. “Can I pass the things out?”

I understand now. “Oh, did you bring papers, too? Are those kind of like ... valentines, maybe?” He nods, appreciative that I have labeled his creations for him and understood their purpose.

In the world of teaching, this is called “approximating.” When children approximate, they replicate a process or action that they have seen or learned, but which they can’t fully create or understand on their own yet. This second child is approximating the first child’s work; while not quite understanding the craft or design, he is able to imitate some of its basic components. He knows it’s not quite right but not exactly why.

First-graders’ lives are filled with approximating—this is how they learn. Each approximation, each practice, each attempt brings them closer to being able to create something on their own. I begin to recognize that as their teacher in a pandemic, I’ve been approximating for the entire year as well.

I spend my days approximating being a healthcare professional. I follow the school safety protocols zealously because I understand what’s at stake, even if I don’t understand the reasoning behind every single rule.

Approximating as an Adult in a Pandemic

In a normal year, my desk would have several students sitting at it. They would be working amid the piles of the paperwork that make for good teaching: running records of reading, anecdotal checklists of notes on each child and their academic strengths and weaknesses, intervention paperwork, letters from parents. This year, my desk feels like a low-budget doctor’s office. I’ve repurposed my normal paperwork into tools for health monitoring. On my district-issued teaching calendar, I dutifully record quarantines, dates when students are cleared to return, days that students were out sick, explanations from families for why the student was out, and notes on the students whose health I am monitoring in class. In normal years, I regularly listen, time and record students while they read aloud to me, and then I analyze their reading errors in what’s called a running record. This year, my running records are about sneezes and coughs: student, time of day, frequency, does it constitute a “recurrent cough” and warrant a referral to the sick room?

The class seating chart sits carefully in its place on the desk; it’s been needed almost every week since winter break as our school nurse contact-traces her way through the room. The seating arrangement should change as little as possible in case we have to track who’s come into contact with whom. Each time I change the seating, I have to update it to the school’s Google Drive for the nurse to use for tracing and quarantines. So much for students choosing their partners or fluid grouping based on students’ changing academic needs—keystones to student independence and excellent teaching and learning. Instead, the students are stuck at their desks for an extended school day of breakfast, class, lunch, class, dismissal. Recess has been permanently canceled due to concerns about social distancing. In a staff meeting on updated health protocols, two-thirds of my team is out sick. The nurse tells me I’m doing a good job following the procedures and keeping the class and myself safe. I feel temporarily reassured. My approximating is working.

I develop a ruse and take our class mascot, Mr. Bear, home with me. A day later, the class is outraged. “Where is Mr. Bear?” they demand.

“He wasn’t feeling well, so he had to stay home. He may need to go to the doctor to get checked out. It’s important to stay home if you aren’t feeling well.” I’m trying to normalize doctors’ visits and medical care for students whose families are—most likely —not insured or are underinsured.

“Do bears get the COVID-19? When will he be back? He really has a doctor?” My fiancée takes Mr. Bear to an urgent care clinic and sends us a photograph of him by the clinic sign. “He’s getting tested,” I report. “His test says he’s negative, but he has to wait until he feels better to come back to school.” The students are deeply interested. Who am I approximating now? Mr. Rogers meets a public health campaign?

I wonder about the right space to inhabit as an educator in a pandemic. What are the lines for privacy, information sharing and advocacy? In a world of alternative facts, what should a teacher tell a 6-year-old about the 2020-21 pandemic world? When we discuss the presidential election in November, I explain how Joe Biden won the election. “That’s not what my mommy says,” a child informs me. So what’s the line in a world of medical misinformation? What do and don’t I discuss in class?

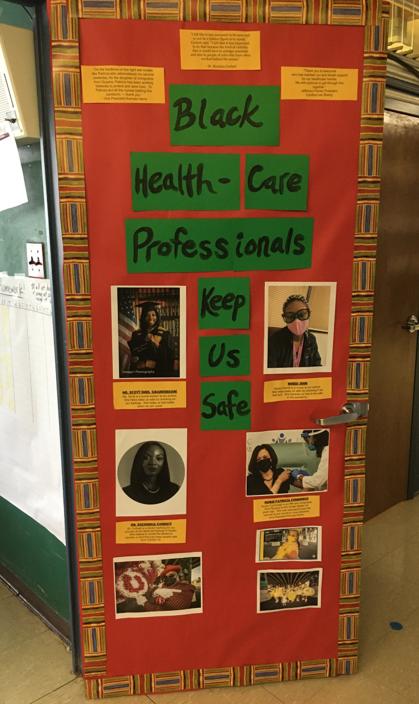

For Black History Month, I decorate the classroom door to show respect and appreciation for the Black healthcare workers in our lives. “Black Healthcare Professionals Keep Us Safe,” my door proclaims. Our school nurse and school social worker occupy places of honor, along with Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, a Black immunologist working at the forefront of developing the Moderna vaccine. I spend a significant amount of time in my friends’ backyard debating if putting up information about the vaccine is “political.” I want to display the City of New Orleans’ public health campaign, in which Black culture bearers of the city say: “SLEEVES UP, NOLA! The COVID vaccine is our shot to get back to normal.” I feel conflicted and frustrated: If I put this on my door, what will the vaccine-averse teachers in the school think? Is this political speech, or is it outreach to underserved communities? In the end, I decide not to post the slogan on the door. It doesn’t seem like we’re ready. “I would rather cross the line of what a teacher is and isn’t allowed to say in school some other time,” I tell myself. “If not to save lives in a pandemic, then what?” my other self wonders back.

It all brings me back to approximating. What if—by the time this pandemic is over—the 6- and 7-year-olds in my class find themselves no longer approximating pandemic safety protocols, but internalizing them, even when they’re no longer needed? What if—in full mastery of pandemic safety—they learn to keep themselves as far apart as possible, they lean away when someone leans close, they no longer offer to share their crayons, they don’t offer to help when someone drops something? As we teach pandemic safety, we try to help students see themselves as individuals in their own safety bubble. But usually, early childhood represents a crucial moment when teachers try to help students focus on more than themselves; good teachers help young students learn to be invested in their community, in their shared life with their schoolmates. Instead, teachers are now stuck enforcing personal, autonomous bubbles in their classrooms. In my darker moments, I wonder: What kind of adults will pandemic kids grow up to be?

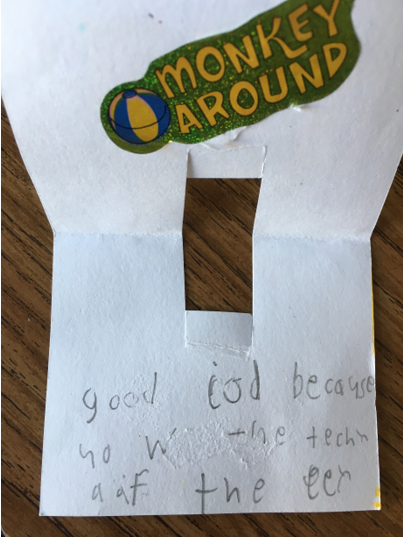

In the end, I know that at least we’re not approximating any feelings this year; the class and I are fully feeling every single step of pandemic education, with its frustrations and complexities. When I return to my desk one afternoon several weeks later, I find a carefully decorated paper wallet. I peel off the sticker that obscures its message: “Good jod because yo wuz the techr aaf the eer.” I hold myself back from critiquing the approximations in writing, spelling and handwriting, and from brainstorming yet another way to help this student distinguish between b’s and d’s. Focus on what’s in front of you, I remind myself. The sincerity isn’t approximated, it’s fully there. And so is my gratitude for this child, this place, this work. Like all of us, I’m just tired of approximating regular life.

- Public Schools Week is February 22-26! Watch a panel featuring the author of this blog, Rosamund Looney, on speaking up for public schools.

- Listen to Rosamund's podcast with the Learning First Aliance here.